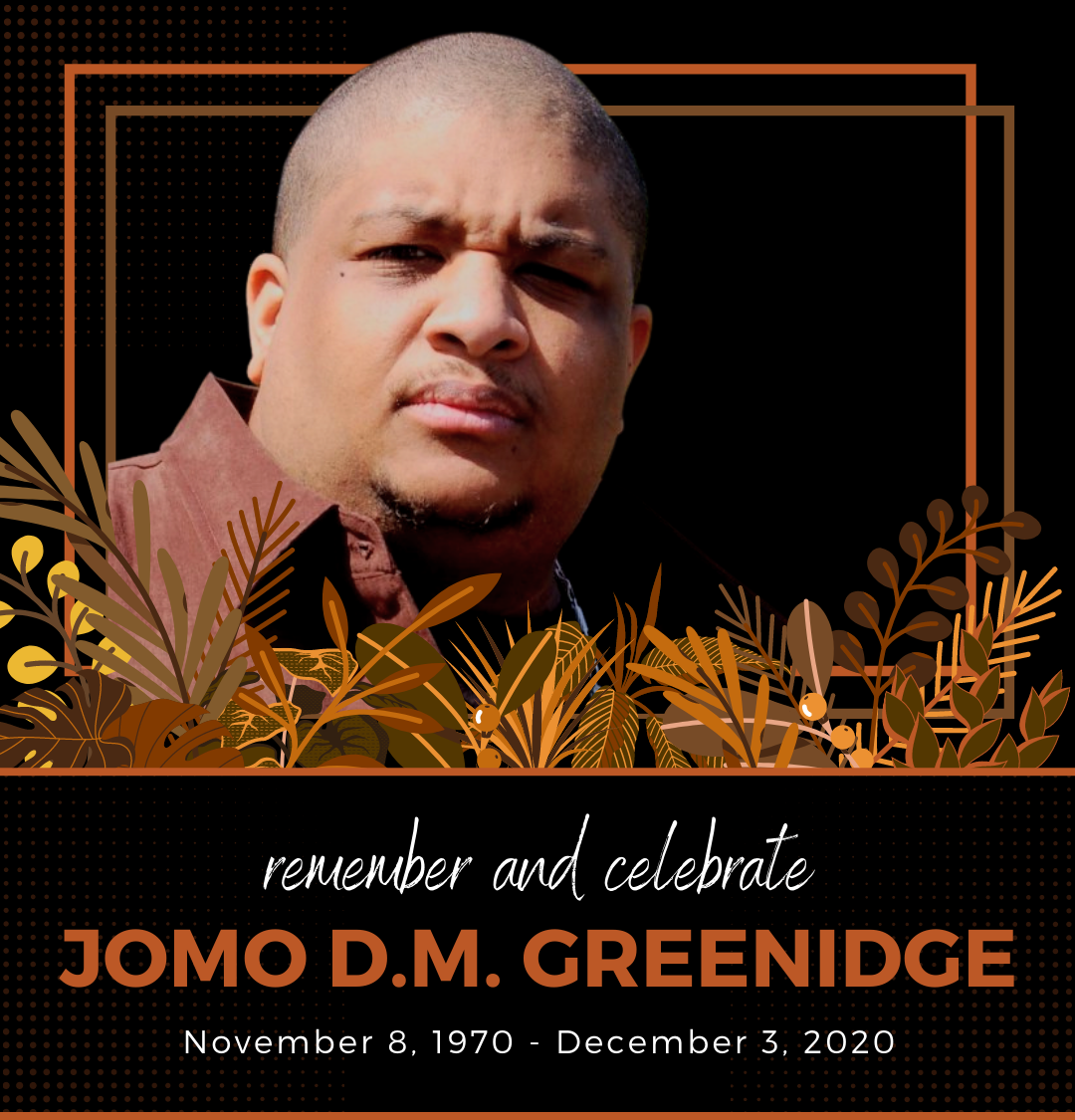

On November 8th 1970, Jomo David Mungai Greenidge was the second of four children born to Henry Greenidge and Esther Whittingham of New York.

Jomo was constantly on the move from his very first steps. For his parents, Jomo’s kinetic energy was easier to manage inside the confines of his family’s Bronx high-rise apartment, but once he made it outside, all bets were off. He liked to move, and move fast.

He spent many happy days playing with his siblings Camille, Rachelle, and Jelani, under the supervision of many loving family members. The family spent a lot of time at church or at Soul Liberation rehearsals, and no matter where he was or who he was with, he played until he dropped – being found on a pew or in front of the kick drum, sound asleep.

Jomo expanded his imagination reading books and hearing stories. He also loved to watch his grandpa Walter Whittingham perform simple magic tricks, and even occasionally tried to duplicate them. Jomo was always trying to learn how things worked, and was known for taking things apart and putting them back together again. It was part of his insatiable curiosity and thirst for knowledge and wisdom, which only grew as he got older. Even as a boy, Jomo was known to ask questions of adults that would stop them in their tracks.

The family moved from New York to Seattle, Washington when Jomo was seven and a short time later, his mother Esther was informed at a parent teacher conference that Jomo was bright and curious, but did not always complete his assignments to the teacher’s satisfaction. When Esther brought several of his supposedly incorrect assignments home to ask Jomo about them, Jomo provided a startling explanation. Because the class was so boring, Jomo took the initiative to invent his own linguistic format, and wrote all of his answers from right-to-left, instead of the standard left-to-right. Flabbergasted by his creativity, Esther went back to the teacher and explained Jomo’s decision, helping the teacher to realize that Jomo was not like the other children. Although it was not always appreciated or understood by his teachers, Jomo’s brilliance led him to invent his own ways of participating.

In 1985 when Jomo was 14, the family moved to Portland into a five bedroom home in the Irvington neighborhood. Unlike his other three siblings – who all selected traditional bedrooms, Jomo opted to live in the basement, surrounded by musical and technical gear, because that’s where he could tinker with his stuff and blast his tunes unbothered. He spent hours on his first computer, an Apple 2e, which was gifted by Tom Skinner, a friend of the family who Jomo affectionately called uncle. During part of that time, he and sister Rachelle attended Fernwood Middle School together, and despite the good-natured teasing he gave her, Rachelle always knew that Jomo had her back. On more than one occasion, other students had tried antagonizing Rachelle in some way, but by the end of the day, they had Jomo to deal with. He was not shy about protecting the people he loved.

In Jr. High, Jomo began running sound for the Disciples Choir as well as the church services at Maranatha Church, where his dad Henry was on staff as associate pastor. Following in the footsteps of his uncle Timothy Greenidge, Jomo learned the values and techniques of sound production, following the axiom that it doesn’t matter how talented the people are onstage if the audience cannot hear them clearly.

His technical aptitude led him to enroll in Benson Polytechnic High School, where he also played offensive line on the football team. He and his friends bonded not only over sports and music, but also over their frustrations about mistreatment from teachers and other authority figures. These experiences caused him to be acutely aware that the educational system was stacked against him and other Black students by prioritizing behavioral conformity over genuine engagement. Jomo’s deep sense of justice was honed through clashes with teachers after being chronically stereotyped and misunderstood. He excelled in mathematics – calling it the language of the universe – and was described by peers as one of the smartest students they knew. As a bet with a friend, he took the SAT his Junior year without studying, and received a perfect math score. Subsequently, he was inducted into Mensa, signifying Jomo as a highly intelligent person and in the top 2% of all-age thinkers. He was also offered numerous invitations to Ivy League schools. Out of sheer boredom during his Senior year, he obtained a job running the IT department at Providence hospital. Jomo went to work during the day and maintained passing grades in all of his school work by studying at night in spite of not attending class. When school officials discovered that his absences were not excused, they decided to make an example out of him, and refused to allow him to graduate.

Nevertheless, Jomo refused to let the failures of the public school system stop him from learning and achieving. All throughout high school, Jomo was involved in alternative learning programs like Saturday Academy and MESA (Math, Engineering & Science Achievement) where he was not only a student but also an instructor for other students his own age and older. This involvement culminated in the summer of 1993, when Jomo earned a certificate leading a summer program teaching dynamic programming to Portland area youth under the tutelage of educator Michael “Chappie” Grice.

While working several computer or software-related jobs, Jomo also expressed his love for music and sound technology by forming a DJ crew called Three Parts and a Fade Productions (3PF) with Trent Aldridge, Durelle Singleton, and Clint “Bleach” King. The 3PF crew, along with friends Bekim Taylor and Jay Mitchell, rocked crowds of high-school and college students at dances and parties all over Portland, Eugene and Corvallis. They played the best of rap, R&B, and a new hybrid sound known as “new jack swing” (shout out to one of their heroes, Teddy Riley). This group shared many wild adventures together and Jomo often invited Jelani or his cousins to join in the fun.

As a pastor’s kid, Jomo experienced the ups and downs of church life, but in his mid-twenties, he responded to a call toward spiritual transformation by enrolling in a Christian discipleship program called The Master’s Commission (MC) located in Spokane, Washington. After graduating from the student program, Jomo joined the MC staff where he mentored future students and impacted the lives of many in the church network.

Not only did he travel with the group across the country on ministry trips, but he was also a leader in the church’s ministry worship team, wrote and arranged original songs, and was instrumental in establishing the MC’s web presence by lending his self-taught technology skills and cutting edge web design in order to expand their reach internationally. All the while, he continued to study the Bible, preach God’s word, and lead others in song. Around the MC, Jomo was known for his infectious laugh, quick wit, sense of humor, honesty, and the ways he selflessly shared himself with others. He felt a deep connection to the MC mission of impacting youth yet he recognized that predominantly white evangelical spaces were not equipped to reach Black youth. His time in the MC ministry was both impactful and costly and he returned to Portland out of a desire to be among Black people and serve his Black community.

Upon returning to Portland, Jomo reconnected at the church of his youth, Irvington Covenant Church, founded by his dad Pastor Henry. After volunteering there, Jomo teamed up with youth pastor Sahaan McKelvey to help pioneer a new format of hip-hop worship called “RepChrist,” where they would rearrange popular gospel and praise-and-worship songs with the language and musical idioms of popular Black music. They collaborated with Jomo’s brother, Jelani, and recruited talented musicians across the area for their events, including luminary saxophonist Eldon “T” Jones, his brother Anthony Jones, drummer extraordinaire, and veteran funk bassist Eddie Ramirez of Spokane. Across the early 2000s, Jomo and Sahaan were very active in Portland’s growing Christian hip-hop scene, not only galvanizing area youth at RepChrist events, but producing a radio show and a series of compilation mixtapes known as “Holy Heat.”

As this was happening, Jomo continued to extend his investment in Black youth outside the walls of the church. He ran the Moore Street Salvation Army Computer Clubhouse, an after school program jointly sponsored by Intel and the Boston Museum of Science. While at the Clubhouse, he developed more relationships with area youth, bonding over their shared interests of sports and video games. After the Clubhouse was shut down, Jomo continued the work, spending a great deal of his own time and money developing a series of programs and events designed to connect with the same kinds of kids who, like him a generation prior, weren’t being engaged in public schools. This marked a shift in his overall approach; rather than trying to get the mainstream educational system to adopt his ideas, he set out to accomplish them himself and spent his time and energy investing in the people and principles he cared about most.

He met Rebecca Greenidge (née Burch) in 2007 and they married in August of 2009. The two of them continued to substantially invest in programs and events designed to help Black youth translate their passions for video games into related career fields. These included the Game It Up Festival, BlackPDX, Brothaman Tech, and its NBA-related spinoff, FieroBall. Jomo desired to help transform the next generation of teenage consumers into the world’s problem solvers – producing content and enabling them to compete in the global marketplace of skills and ideas. With Jomo’s guidance, these ideas were brought forward with the support of many students who he mentored – most notably, the “J5 Crew”: Jamal Abdullah, Jordan Clavon, Jose Garcia, Jacoby Kelley, and Jerry Tatum.

With a similar entrepreneurial drive and thirst for racial justice, Rebecca proved an excellent match for Jomo. They shared a deep union – strengthening and challenging each other while sharing an irreverent sense of humor. Jomo became a father when their family of two became a family of four with the addition of Master (aka MJ) and Jaleo; and also for a time, his daughter Ava – making them five. Jomo loved being a father and tirelessly sought to build his children toward their greatest sense of self while always reminding them that “Black is beautiful”. He loved spending time with his children playing card and video games, making up songs, telling stories – real and imagined, going on drives and various trips together, encouraging each child’s personal interests, sharing a love of good food, and having the hard conversations about what it means to grow up and be a positive force in their Black community. He was thrilled to become a grandfather for the first time in October of 2020 when Master’s son, Dae’Jayn was born.

Amidst family life, Jomo continued to build Mungai Media – an umbrella company housing his layered expression of himself and his love for Black Portland. He also partnered with Rebecca to launch JORE Consulting, a firm devoted to the abolition of the system of white dominance. One of Jomo’s most passionate projects was a site he founded called BlackPDX, designed to highlight the businesses, artists and stakeholders of Portland’s Black community. Both BlackPDX and JORE Consulting were highlighted on OregonLive.com in 2020, as the Black Lives Matter uprising amplified the injustice of police brutality while demanding human rights for Black people.

Jomo’s skills were broad – and while his ultimate goal was to uplift Black people, he could also be found building websites, designing graphics for many different mediums, mentoring youth as well as adults of all ages, brainstorming ideas and strategies, writing articles, fanning the flame of other Black creatives and leaders often from behind the scenes, bringing people together and connecting them at the right time…we could go on. He lived in such a way that has left a huge hole in so many of our lives – a true living legacy.

Two years before his death, Jomo articulated what he wanted his legacy to be; that He was a good dad, a good husband, he loved his community, he loved Jesus, he loved to build, he was a creative, and he believed in Black youth.

He accomplished all of that, and then some.

The world may have not been ready for him, but Jomo Greenidge helped make the world better.

Jomo was preceded in death by his mother Esther Whittingham and his nephew and godson Jeremiah Howell. He is mourned by his wife Rebecca Greenidge, sons Master and Jaleo Greenidge, grandson Dae’Jayn Master, siblings Camille Bass (Lowell), Malaika Rachelle Thompson (née Greenidge) (Darnell), Jelani Greenidge (Holly), father Henry Greenidge (Kathy), a large extended family of aunts, uncles and cousins, as well as a community of Black people – both local and far away, for whom he took every opportunity to celebrate, honor and uplift.

Jomo’s legacy lives on through his projects Dignity and Pride, FieroBall, BlackPDX, and JORE Consulting – as well as the many ways we are different people because he loved, challenged and inspired us along the way.